New research shows hard-hitting campaigns can help prevent drinking during pregnancy

New research released today is putting alcohol use during pregnancy in the spotlight, prompting calls from public health experts for ongoing investment in hard-hitting campaigns to support alcohol-free pregnancies.

The new study, published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Heath, analysed adults’ views on alcohol and pregnancy to evaluate the impact of a public education campaign that aired in Western Australia from January 2021 to May 2022.

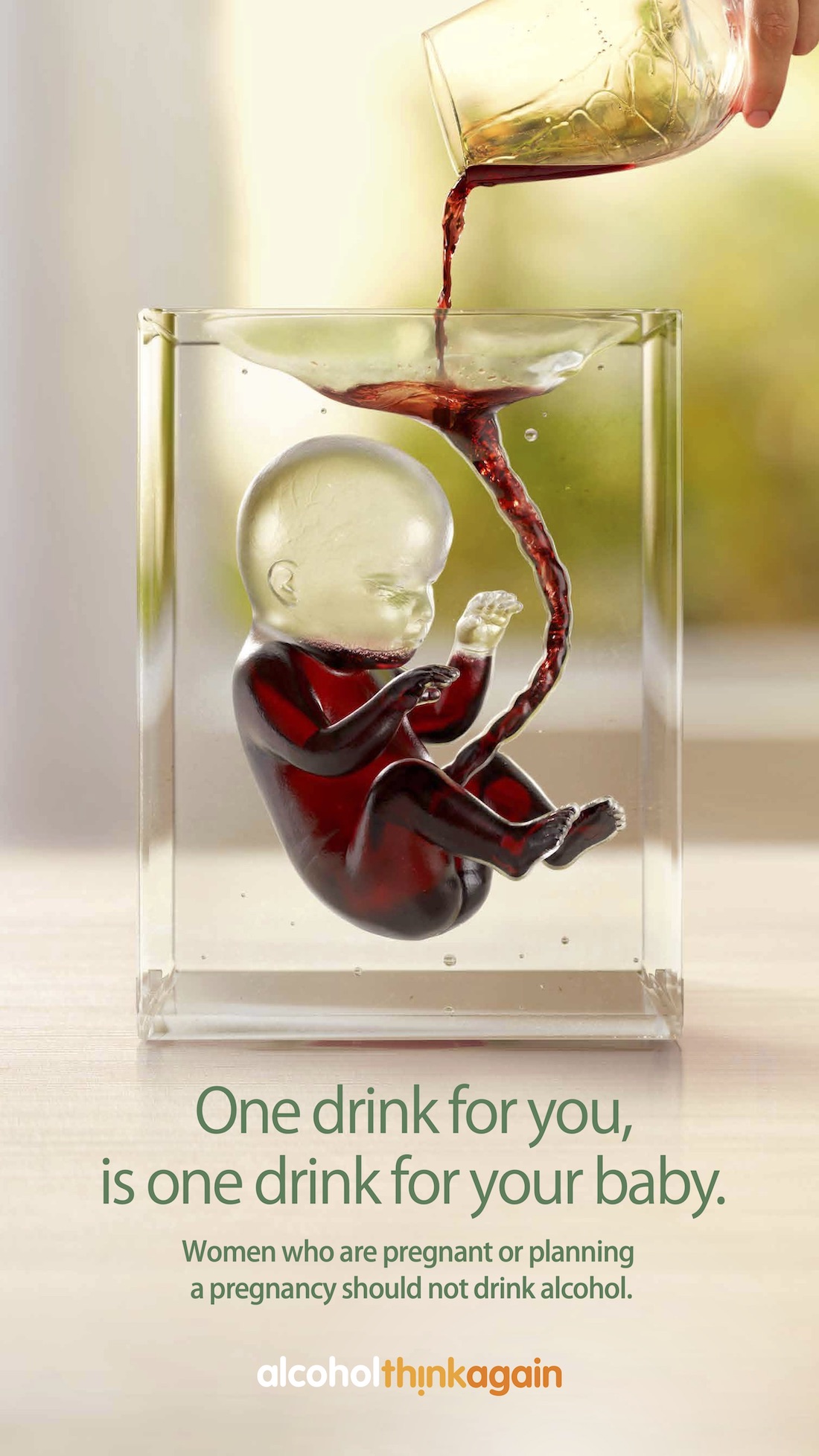

The “One Drink” campaign, developed by the WA Mental Health Commission in collaboration with Cancer Council WA, features a video of a baby-shaped glass being filled with red wine to illustrate that any amount of alcohol a mother drinks, the baby drinks too. The campaign, created by 303 MullenLowe Perth, has recently recommenced airing in WA.

Public health experts say the research findings suggest many Australians of childbearing age do not understand the risks associated with alcohol use during pregnancy but are much more likely to abstain when informed of the risks.

Lead author Prof Simone Pettigrew from The George Institute for Global Health says there is no safe level of alcohol use during pregnancy, and the community has a right to know the facts so they can make an informed decision.

“Previous research has found that around 35 percent of Australian women use alcohol at some stage during their pregnancy,” she said.

“Similarly, in this study we found that before seeing the campaign, almost one-third of men and women aged 18 to 45 were confused about the risks and thought it was okay for women to drink some alcohol during pregnancy.”

Prof Pettigrew says there haven’t been many mass media campaigns about pregnancy and alcohol, and therefore there is limited evidence available about their impact.

“This research was an important opportunity to evaluate a distinctive campaign that ran in WA and see how successful it was,” says Prof Pettigrew.

To evaluate the campaign, researchers surveyed male and female Western Australians of childbearing age, both before and after the campaign ran.

“We found that 76% of survey respondents recalled seeing the campaign. We also uncovered really positive signs that the campaign would help dissuade pregnant women from drinking,” Prof Pettigrew says.

“Additionally, we found that after the campaign had aired, 95% of women reported intending to abstain from drinking when pregnant – and both males and females were more likely to agree that pregnant women shouldn’t drink any alcohol.

“We had previously found that one in two people who viewed the campaign agreed that it contained new health information. This latest research suggests that potential mothers are likely to stop drinking if they are well informed of the risks.”

Prof Pettigrew added that the latest research should send a message to Government about the need to continue to fund these types of confronting, attention-grabbing campaigns.

“There is often contention around whether hard-hitting health campaigns are effective, but this is one of the best campaign evaluations I’ve seen. It shows that campaigns with strong imagery, clear health warnings and new information about pregnancy and alcohol are an effective, worthwhile investment.”

Adjunct Prof Terry Slevin, CEO, Public Health Association of Australia says alcohol is still one of the biggest public health challenges in Australia.

“Alcohol isn’t just an issue in pregnancy, but also a significant public health challenge when it comes to mental health and injury. It also plays a role in over 200 chronic health problems including cardiovascular disease, cancers, diabetes, nutrition-related conditions, cirrhosis, and overweight and obesity.

“We need comprehensive Government action to address the negative impact Australia’s drinking culture continues to have. As well as hard-hitting health campaigns, we need nation-wide minimum alcohol pricing, controls on availability, marketing restrictions to protect children, and warning labels.”

Credit: Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. All articles are open access and can be found here.

3 Comments

Still a great campaign from two of the best Steve’s

Has there been any reduction in FASD rates on WA? Isn’t this what we should be measuring?

An awareness campaign is likely to see an increase in the rates of diagnosis of FASD. Not because more people are drinking but because more become aware of the risks of alcohol consumption and the impacts at any stage of a pregnancy. FASD is under diagnosed, misdiagnosed as other neuro-divergent conditions and is often missed in the diagnostic process for fear of stigma and blame. The public health message needs to explain the importance of abstinence from Alcohol if people are trying to become pregnant, or if they are consuming alcohol and not using reliable contraception. A large percentage of pregnancies are unintended/unplanned and alcohol exposure in the early weeks of a pregnancy, before someone even knows they are pregnant is a critical time for the developing fetus. Alcohol is normalised as part of our Australian culture and FASD will continue to occur until the importance of not drinking any alcohol from the moment someone stops using contraception is key. FASD can occur wherever and whenever alcohol is consumed, at any stage of a pregnancy. This lifelong disability does not ‘just’ occur where high volumes of alcohol are consumed regularly, nor does it only affect certain population groups. We need to de-stigmatise FASD so that appropriate supports and interventions can be put in place early to help individuals and families to achieve their best outcomes.